Dive Brief:

- Delaying the catheter ablation of patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) by up to 12 months has no effect on arrhythmia-free survival in the year after treatment, a randomized clinical trial found.

- The study randomized 100 people with symptomatic AFib to undergo catheter ablation within one month of recruitment or 12 months after recruitment. Freedom from recurrent arrhythmia was the same in both cohorts 12 months after treatment.

- While other studies of medical devices such as Medtronic’s Arctic Front have made the case for an ablation-first approach to AFib, the new trial suggests physicians have a window in which they can treat patients medically without causing worse health outcomes.

Dive Insight:

A recent study showed that ablation is a more effective first-line treatment than antiarrhythmic drug therapy. With a meta-analysis and claims data study finding that patients who are treated earlier have better results, momentum has built behind the case for using ablation as early as possible.

Early treatment could be a boon for medtech companies such as Boston Scientific and Medtronic, but is potentially challenging for healthcare systems, some of which have waiting lists that require patients to wait months for treatment. The new study suggests waits of up to a year will not harm patients.

One year after ablation, 56.3% of patients treated after one month were free from recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 58.6% in the delayed ablation group. The difference was not statistically significant. The researchers also found no significant differences across secondary endpoints that looked at the median AFib burden, both across the whole population and in the paroxysmal and persistent subgroups.

With the use of antiarrhythmic drugs the same in both arms too, the study found no benefits to treating patients with ablation earlier. The relatively small size of the study, plus slight imbalances between the baseline characteristics of participants in the two cohorts, raise some questions about the findings, but the study has still weakened the case for urgent ablation of AFib.

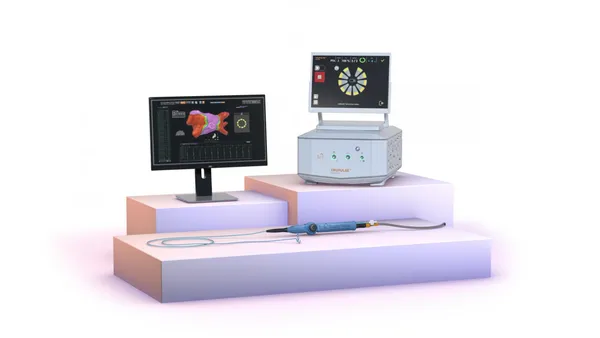

The data come as new ablation devices threaten to shake up the market. The Medtronic study that made the case for first-line ablation used a cryoballoon. Other devices use heat to treat AFib. Now, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and others are aiming to establish pulsed field ablation devices that may be safer than established cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation treatments.