CHICAGO — Too often, cancer has a way of evading treatment. Tumors that were held in check begin to spread anew, forcing doctors to try different drugs in a desperate race to keep malignant cells from multiplying.

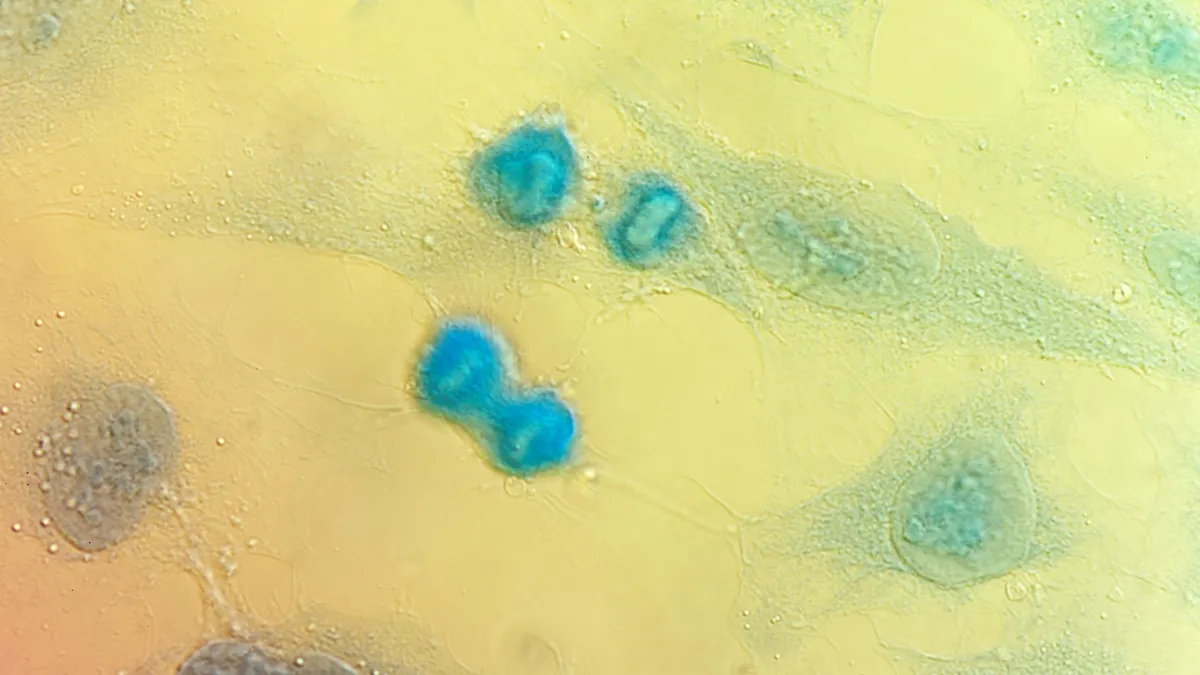

For a common type of breast cancer, this usually happens because of changes in a gene called ESR1. Mutations there can drive cancer growth even as physicians’ first choice of therapy chokes off the resources that tumors had relied on to survive.

Afterwards, the prognosis for patients gets worse. Multiple second-line medicines exist, but “their benefit is limited, quality of life decreases and survival rates are low,” according to Nicholas Turner, director of clinical research and development at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London.

New study results from Turner and others show an experimental drug from AstraZeneca, camizestrant, can help sustain the benefit of first-line therapy. Unveiled Sunday, their research found that, once ESR1 mutations are detected, swapping out a standard component of that initial regimen for AstraZeneca’s drug reduced the risk of disease progression or death by more than half.

Data from the study, which AstraZeneca funded and in February said succeeded, will be presented Sunday afternoon at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting.

“Patients have an urgent need for new treatments that can prolong time on first-line therapy and delay disease progression,” Turner said in a statement provided by ASCO.

In their clinical trial, Turner and colleagues enrolled 3,256 people with advanced breast cancer positive for hormone receptors but negative for a protein called HER2. These individuals are typically treated with a kind of hormone therapy known as an aromatase inhibitor along with another type of targeted drug that interrupts cancer cell division.

Participants in the study were monitored via blood tests for the emergence of ESR1 mutations, which were eventually detected in about 550 people. Three-hundred and fifteen were then randomly assigned to receive camizestrant instead of the aromatase inhibitor or to continue on with their initial regimen. These patients continued to receive those targeted drugs, “CDK 4/6 inhibitors.”

Patients who were switched to camizestrant had a 56% lower risk of their cancer progressing or killing them than those who continued on, researchers calculated. Put another way, people in the camizestrant group lived a median of 16 months without disease progression or death, compared to 9.2 months for those in the control arm.

Data also showed camizestrant helped maintain quality of life for longer than did aromatase inhibitors, too.

Researchers continue to follow study participants to measure differences between the groups in overall survival, but don’t yet have enough follow-up data to determine whether there is a benefit on that score.

Less than 2% of patients in either group discontinued treatment due to side effects, which, for camizestrant, were consistent with what AstraZeneca has observed in prior testing.

Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative tumors are the most common type of breast cancer, accounting for an estimated 70% of cases. Hormone receptors provide a dock for estrogen, which spurs the tumor to grow. In first-line therapy, hormone therapy shuts off estrogen signaling by either gumming up hormone receptors on the surface of breast cancer cells, or by blocking the body from making estrogen.

But about 40% of patients whose breast cancer is responsive to hormone therapy develop ESR1 mutations during their initial therapy, according to an estimate cited by ASCO. Research done a decade ago at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center discovered that ESR1 mutations change the shape of the estrogen receptor, essentially flipping it “on,” whether or not cancer cells continue to receive an estrogen growth signal.

Camizestrant offers a way to get ahead of that change by breaking down the estrogen receptor entirely. It’s one of a new crop of so-called selective estrogen receptor degraders, or SERDs, that are taken orally rather than injected like the drug fulvestrant, which has been a staple of breast cancer treatment for decades.

One member of this fresh class, Orserdu, won U.S. approval in 2023. Others from Eli Lilly and Roche, as well as a different kind of degrader from partners Pfizer and Arvinas, are in late-stage testing. Data from a Phase 3 trial involving Pfizer and Arvinas’ vepdegestrant in people whose hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer progressed following initial treatment were presented at ASCO Saturday.

The setting envisioned by camizestrant’s trial is one step earlier, subbing in a SERD before initial disease progression to allow patients to remain on first-line therapy longer.

“When patients progress on scans, we’re already behind. We’ve already lost control, in some sense,” Eleonora Teplinsky, head of breast and gynecologic medical oncology at New Jersey’s Valley-Mount Sinai Comprehensive Cancer Care, said in a press conference held by ASCO. “An early switch approach, before we see disease progression on imaging, [allows] us to stay ahead of the curve.”

Switching early requires regular monitoring, which Turner and his colleagues accomplished by using “liquid biopsies,” tests that pick up fragments of tumor DNA circulating in the blood. While these are relatively expensive, Turner said he hopes insurance would cover them should camizestrant win approval in the tested setting.

Clearance would also change doctors’ testing practice. Soon after Orserdu won U.S. approval, ASCO updated its treatment guidelines to recommend testing for ESR1 mutations following disease progression or recurrence. Camizestrant’s benefit lies in delaying that progression, making active surveillance beforehand essential.

“The difference here is this serial monitoring for evidence of the evolving mutation,” said Julie Gralow, an oncologist and ASCO’s chief medical officer, at the press conference.

Establishing reimbursement and updating guidelines will be important to that goal, acknowledged Mohit Manrao, a senior vice president in AstraZeneca’s U.S. oncology division. “The good part here is that the test exists,” he added “It is already being done at the point of progression,” he said.

AstraZeneca plans to use the data presented at ASCO to request regulatory approval. It is also studying replacing aromatase inhibitors with camizestrant upfront, rather than waiting for ESR1 mutations to emerge. Two other trials are examining camizestrant’s potential in early breast cancer.