Next to big-name brands like Abbott Laboratories and Becton Dickinson, a swath of lesser-known companies are selling COVID-19 tests to schools, hospitals and corporations.

Buoyed by the pandemic, these small firms and startups have seen their revenue multiply from selling the tests, but as large institutions wind down mass testing programs, many of these companies are having to rapidly change the way they do business in order to survive.

With the need for over-the-counter antigen tests unlikely to wane soon, according to public health experts, some firms are teaming with drugstore chains and distributors to target consumers. Others are leaning into diagnosing other diseases.

All of them are considering what will happen at the expiry of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency-use authorizations for most of the tests once the public health emergency ends.

“The paradigm for testing has shifted most definitively to the home right now,” said Bala Raja, CEO of Clip Health, a testing firm created in 2014 with funding from Y-Combinator and the National Institutes of Health.

“There is a slowdown in demand across all of these segments — not to say that it doesn't exist, but over the last several months, it's been a gradual waning demand in traditional healthcare settings or where somebody has to go out and stand in a line, or go to a drive-thru and get a swab collected and get results,” Raja added.

The Silicon Valley-based company’s tests are used in doctors’ offices, urgent care settings and some pharmacies, as well as by companies that have a license to provide testing for events and employers. Now, seeing demand for testing shift to the home, Clip Health plans to seek authorization for an at-home antigen test with a reusable reader.

“We see COVID being a meaningful part of our business for at least the next couple of years” despite the shift, Raja said.

Onus for testing shifts to the home

Nate Hafer, assistant professor of molecular medicine for UMass Chan Medical School, said most testing programs run by schools and businesses for employees have ended, at least in Massachusetts.

“With the availability of over-the-counter testing being much more commonplace these days, I think people are passing that [responsibility] to individuals,” Hafer said, adding that classic market forces seemed to be a driving factor in people’s test choices.

“The tests people can get for free are obviously very attractive,” he added. But when those are not available, “the tests at the best price point at the supermarket, or drug store … tend to be what people are grabbing.”

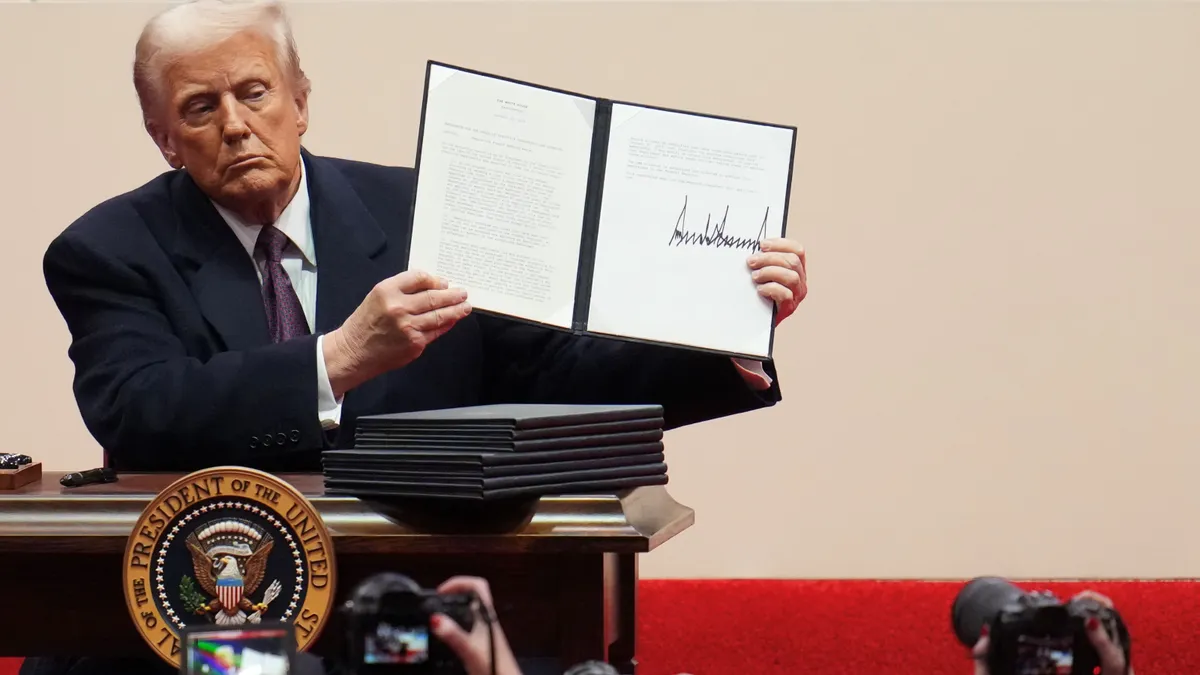

Companies also face less funding from the U.S. government to expand testing capacity, after Congress reached an impasse on a COVID-19 funding deal last month. The Biden administration said it would repurpose about $10 billion in funding from testing to buy more COVID-19 vaccines and treatments.

Ashish Jha, who leads the White House response to COVID-19, said in a June press briefing that as a result, domestic testing companies are laying off workers, shutting down production lines and may even sell off equipment.

Small companies in particular face a challenge as many of the large government and corporate testing contracts have already been signed. As rapid tests became more prevalent starting in February, smaller companies needed to provide some kind of niche product or position themselves differently, said Tinglong Dai, a professor of operations management and business analytics at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School in Baltimore.

Time for a pivot?

“They could pivot to other tests — flu tests — a lot of other kinds of tests,” Dai said. “The whole idea that people can test for disease at home, I think it's incredible. Before the pandemic, it was unthinkable.”

LumiraDx, a London-based startup founded in 2014 and whose tests are made in the U.S. and Great Britain, also counts pharmacies and U.S. health systems among customers for its COVID-19 antigen test.

Chief Product Officer Pooja Pathak said that while demand for screening for events and travel has been getting smaller, the company is seeing steady demand from its healthcare customers.

The firm names CVS as its biggest customer, which doesn’t sell the tests over the counter but offers rapid tests administered by a pharmacy technician.

“As COVID testing has gone up and down, we’re subject to those kinds of shifts in case rates, but maybe less so [than other companies],” Pathak said, adding the company’s work with health systems and pharmacies had provided stability.

LumiraDx also is in the process of developing an at-home testing system, but it’s not yet authorized by the FDA. It’s also grappling with changes in the diagnostics regulations in the European Union, the company disclosed in a June prospectus. It didn’t break down sales by country.

Balancing demand and cost

Some smaller testing companies, seeing demand for at-home testing surge during the previous waves, seized the opportunity to go public. Cue Health, a San Diego-based company that makes a home molecular test, went public in September of 2021. SD Biosensor, a South Korea-based company that makes home antigen tests, began trading on the Korea Exchange in July of last year and recently struck a deal to buy diagnostics company Meridian Bioscience for $1.53 billion.

Cue Health saw its revenue balloon from $23 million in 2020 to $618 million in 2021, but it recently laid off 170 workers, citing economic challenges and the U.S. government’s decision to reduce funding for COVID-19 testing. The company won a $480.9 million contract with the Department of Defense in 2020, though it had to get an extension to manufacture enough test cartridges and readers.

Now, most of its business has shifted to private sector customers. In the first quarter of 2022, Cue brought in $179.4 million in revenue, less than 1% of which came from the public sector. It expects a slower second quarter, forecasting sales of $50 million to $55 million. Under an agreement with grocery store chain Albertsons, Cue CEO and co-founder Ayub Khattak said in an earnings call in May that the company had placed COVID-19 tests in more than 1,000 Albertson’s pharmacies.

The molecular test, which is Cue Health’s sole product on the market, also costs much more than antigen alternatives. Bought as standalone products, its test reader costs $249 and a pack of three test cartridges costs $195. Cue and other makers of at-home molecular tests say the better accuracy of molecular tests justifies the higher price.

Seeking FDA clearance

Most COVID-19 tests currently on the market only have an emergency use authorization, meaning that after the public health emergency ends, they can no longer be marketed.

It won’t be instantaneous — the FDA has indicated that it plans to give test-makers 180 days’ notice before their EUAs are terminated — but the agency recently encouraged companies to go ahead and seek regulatory clearance for their tests.

“At some point, the switch is going to flip and that's going to be the expectation that people have,” UMass’ Hafer said.

New tests would go through the de novo clearance pathway, which includes controls to ensure a device’s safety and effectiveness. Where an FDA-cleared test already exists, diagnostics companies could use the 510(k) pathway, where they merely need to demonstrate “substantial equivalence” to an existing approved device.

A PCR test developed by BioFire Diagnostics got de novo clearance earlier this year, but no rapid antigen tests have yet gone through full FDA review.

Cue filed with the FDA for de novo clearance of its home molecular test in May. Some other test makers are taking a wait-and-see approach.

Clip Health’s Raja said that the company was awaiting guidance from the FDA on what the agency expects to see in a 510(k) submission and when the 180-day clock is going to start.

Companies that already have an emergency authorization for a COVID-19 test should submit a transition plan to be able to continue to market their tests as they seek clearance, the FDA said in a meeting earlier this year.

Future for multiplex testing

One advantage for the startups is that when it comes to buying a test from the store, consumers don’t seem to care much about which company made them, public health experts say.

“I think a lot of it has to do with availability. Most of the population doesn’t differentiate between different brands,” said Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security at the Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. “I just pick whatever’s on the shelf.”

Looking to the future, Adalja expects demand for home antigen tests will remain steady. He and Hafer of UMass say the future for test manufacturers may well lie in creating at-home kits, known as multiplex tests, that can test for multiple respiratory viruses.

Cue is working on a multiplex test for flu and COVID-19. Lucira Health, another testing startup with an at-home molecular test, is starting to manufacture a combination flu and COVID-19 test. It plans to seek an EUA first and start distributing the tests this fall, CEO Erik Engelson said.

“Prior to COVID-19, you could only test for HIV at home. That approval was a 10-year process,” said Adalja. “That’s the next phase of this, to take the momentum for home testing, and apply it to a broader range of issues, a broader range of pathogens.”