Dive Brief:

- ZIP codes with higher proportions of Black, Hispanic and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients have lower rates of transcatheter aortic valve replacement, according to an analysis of Medicare claims data.

- The analysis, which was published in JAMA Cardiology, looked at TAVR use in 25 metropolitan areas. While earlier work has shown geography is a barrier to TAVR access, the new study demonstrates that uptake varies even among people who live near to hospitals that do the procedure.

- Rates of TAVR correlated to zip code-level changes in household income, race and ethnicity, leading the researchers to identify a need to tackle multiple barriers to high-quality care. However, a note from JAMA Cardiology editors accompanying the analysis made the case that more research is needed on the subject. "Is it possible that there are race-based biases impacting TAVR at the patient level? Yes. Is it proven? No," the authors wrote.

Dive Insight:

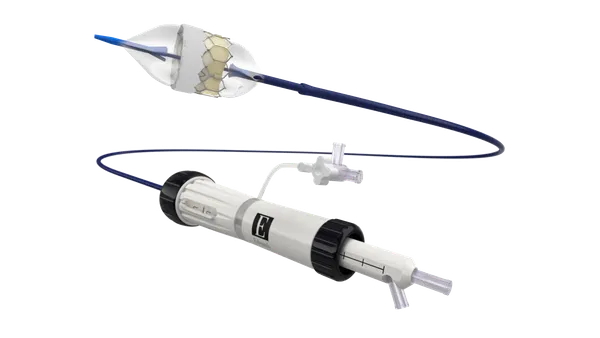

The concentration of TAVR sites in urban areas is a barrier to access for patients living in rural areas that has been debated throughout the short history of the procedure, with CMS trying to balance the pressure for local treatment against the need to ensure sites are busy and experienced enough to deliver good outcomes. Now, researchers have shown geography is far from the only barrier.

"Within major metropolitan areas in the U.S. with TAVR programs, ZIP codes with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic patients and patients with greater socioeconomic disadvantages had lower rates of TAVR, adjusting for age and clinical comorbidities," the authors concluded.

In the highest income bracket, the age-adjusted rate of TAVR was 318 per 100,000 beneficiaries. The rate in the lowest income bracket was 170 per 100,000 beneficiaries. TAVR procedures per 100,000 beneficiaries fell for each $1,000 drop in median household income. Similarly, each 1% increase in the number of Black or Hispanic people was associated with a 1% drop in TAVR procedures.

The analysis covers 2012 to 2018, a period in which TAVR was a relatively new, emerging technology. However, the idea that use of the procedure may normalize across different populations over time is refuted by data on the older surgical aortic valve replacement approach. The researchers saw similar disparities in uptake of SAVR and TAVR.

The similarities of the SAVR and TAVR data suggest there may be substantial challenges to overcome, according to the researchers. Rather than being specific to TAVR, the findings may represent far broader "structural, racial, ethnic and socioeconomic barriers to high-quality care." The study looked at the problem on that level, instead of trying to assess bias in patient-physician interactions.

JAMA Cardiology editors in their note accompanying the analysis acknowledged, as the study's authors imply, that "access to and referral for high technology procedures predicated on team-based decision making are subject to bias." However, they argued that race per se is not the sole culprit explanation.

"Until more research and research methodology evolve, we must do more to recognize our possible biases and concomitantly exercise caution before concluding race-based disparities in the utilization of TAVR. We can be empathic but we must also be sure," the editors wrote.

Other researchers have previously identified racial disparities in TAVR use across the U.S. as a whole, rather than just in major metropolitan areas, revealing that minorities are underrepresented among patients undergoing the procedure nationally.

The Journal of the American College of Cardiology in August published a study that found a concentration of TAVR sites in certain urban areas was linked to lower annual volumes and an increased risk of mortality. The authors made the case that the proliferation of sites in urban regions that already have at least one TAVR program has left rural regions of the country unrepresented, potentially contributing to "worsening disparities of care."